Deep Dive: Geopolitical Disorder

Clarity for leaders navigating geopolitical change—without noise.

Navigating a Fragmented Future: Insights from Ian Bremmer, John Mearsheimer, Parag Khanna, and Amy Webb

TL;DR: - Strategic Synthesis 2026

In a world of geopolitical volatility, structural exhaustion, re-networked globalization, and exponential tech disruption, four world-class thinkers offer a 360° strategy lens:

- Ian Bremmer warns of a fragmented “G-Zero” world where U.S. political volatility is now the primary source of global risk.

- John Mearsheimer argues great-power rivalry is back — with Ukraine, Taiwan, and U.S. overstretch marking the return of structural realism.

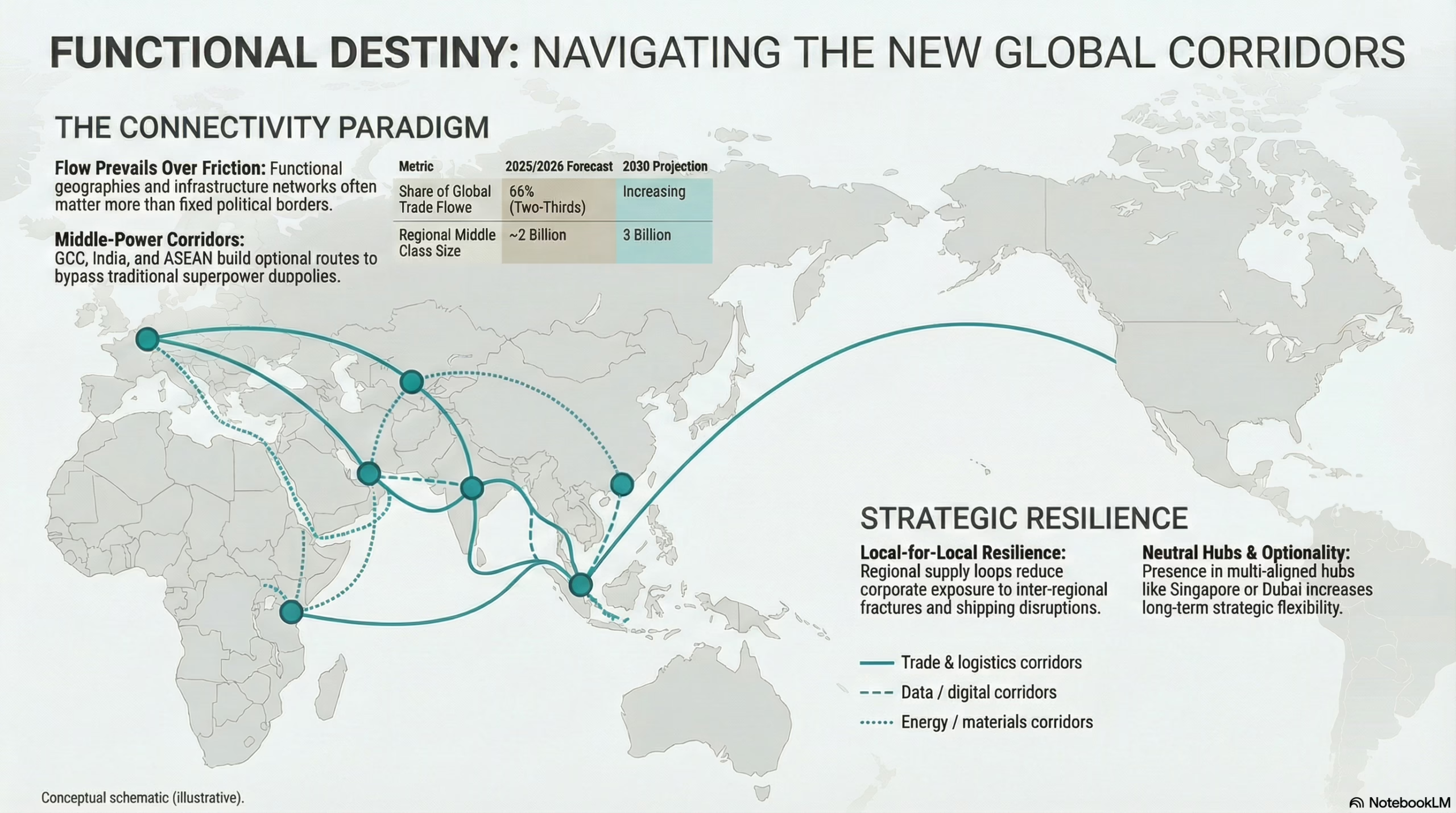

- Parag Khanna highlights the rise of autonomous connectivity corridors, where “Middle Powers” bypass superpower duopolies and build new hubs of influence.

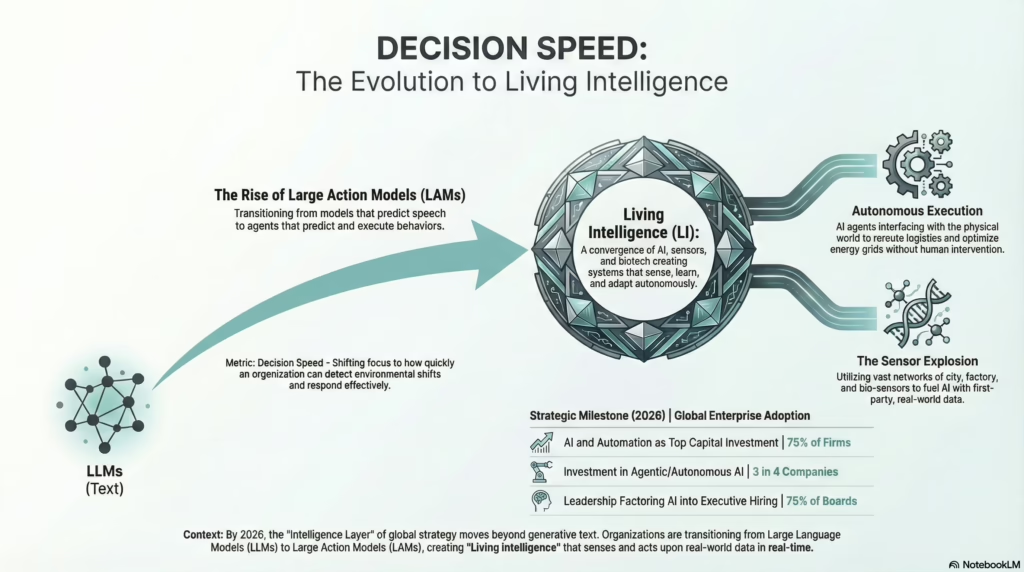

- Amy Webb shows how “Living Intelligence” — the convergence of AI, sensors, and biotech — is redefining strategic foresight, speed, and agency itself.

Bottom Line for Leaders: Strategic clarity in 2026 means integrating all four lenses. Surviving the dialectics of disorder requires hedging volatility (Bremmer), auditing hard power limits (Mearsheimer), building networked resilience (Khanna), and accelerating intelligent systems (Webb).

Executive Question: In a post-unipolar world, how many strategic realities can your board synthesize at once?

Looking for speakers on this topic? → See our curated shortlists for Geopolitics keynote speakers or request your own tailored shortlist

The Dialectics of Disorder: A Quad-Axis Framework for the 2026 Boardroom

Introduction: Navigating a G-Zero World in 2026

In 2026, the global operating environment has decisively transitioned into what political risk expert Ian Bremmer calls a “G-Zero” world – a chaotic international system with no single hegemon, where power is unconstrained by shared rules and alliances are fragile. The brief post-Cold War “unipolar moment” is a distant memory; instead, geopolitical stability now hinges on the unpredictable interplay of multiple great powers and regional actors. For corporate leaders, this translates into unprecedented strategic uncertainty. As Bremmer notes, “2026 is a tipping point year… the U.S. will be the principal source of global risk this year” – a stark warning that the very nation which built the post-1945 global order is now unwinding it from within.

Amid this disorder, making sense of the future requires synthesizing divergent perspectives. Four renowned strategists – Ian Bremmer, John Mearsheimer, Parag Khanna and Amy Webb – each shine a light on a critical dimension of our world’s transformation. Ian Bremmer’s lens is process risk, capturing how political upheavals (especially within the United States) are triggering immediate volatility. John Mearsheimer's structural realism provides the foundation, further refined by Alberti Romani's analysis of the 'metabolic limits' and 'metabolic exhaustion' of U.S. state capacity. Parag Khanna provides a connectivity intelligence outlook, showing how new networks and regional “middle powers” are reshaping globalization. Amy Webb adds quantitative foresight, foreseeing how technology – from artificial intelligence to biotech – is accelerating and redefining decision-making. These perspectives are distinct, yet together they form a quad-axis strategic framework that can help C-suite executives achieve one overarching mandate in 2026: “Clarity, not urgency.” In a world of swirling crises, leaders must resist knee-jerk reactions and instead cultivate clarity – a deep, analytical understanding of risks and opportunities – as the basis for resilient strategy.

This comprehensive report integrates the four experts’ latest insights into a single playbook for senior decision-makers. The goal is to leverage “connected intelligence” – combining human expertise across domains with data-driven foresight – so that companies can proactively navigate geopolitical volatility, power shifts, functional connectivity, and technological disruption in tandem. Each section examines one or more of the axes in this quad-framework, concluding with strategic implications for building resilience, from supply chain localization to narrative leadership. The tone is deliberately perspective-neutral and analytic – akin to a McKinsey or Harvard Business Review briefing – to underscore how each thinker’s viewpoint, even if rooted in their own ideology, contributes to a fuller picture. By the end, a CEO or board should see how these four complementary perspectives can be harnessed to formulate strategy that is both bold and grounded: turning the dialectic of disorder into actionable intelligence for competitive advantage.

I. The American Crisis and Global Connectivity — Domestic Volatility vs. Functional Destiny

The global strategic environment in early 2026 is defined by a collision between traditional geopolitics and emerging functional networks. Nowhere is this clash more evident than in the role of the United States. Once the architect and “underwriter” of world order, the U.S. has become, in Bremmer’s words, “the principal agent of risk” on the global stage. A profound American political crisis – a system-level upheaval in U.S. governance – is radiating instability outward, even as new constellations of countries and supply chains knit the world together in novel ways. This section examines three powerful forces shaping this dual reality: (1) the aggressive U.S. pivot to hemispheric resource securitization under the so-called “Donroe Doctrine”; (2) the structural limits of American power as interpreted through Mearsheimer’s realist audit; and (3) the rise of resilient autonomous corridors of trade and infrastructure, encapsulated by Khanna’s “connectivity as destiny” thesis. Together these dynamics pit domestic volatility vs. functional destiny, forcing leaders to navigate both a fracturing geopolitical map and an integrating global network.

The “Donroe Doctrine”: From Global Policeman to Hemispheric Enforcer

A pivotal inflection point arrived on January 3, 2026, when the United States launched “Operation Southern Spear,” a covert raid that captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro in Caracas. This stunning move – a literal regime change by U.S. special forces in the dead of night – heralded the formal debut of what President Trump’s administration has branded the “Donroe Doctrine.” The term (a portmanteau of “Donald” and “Monroe” Doctrine) signals a revival of the 1823 Monroe Doctrine’s logic of American primacy in the Western Hemisphere, but with a modern, hard-edged twist. “Trump has already branded his approach to the Western Hemisphere the ‘Donroe Doctrine.’ It’s his version of Monroe’s assertion of primacy – except where Monroe warned European powers to stay out of America’s neighborhood, Trump is using military pressure, economic coercion, and personal score-settling to bend the region to his will,” Bremmer explains. In essence, the U.S. is abandoning its post-WWII role as global policeman in favor of a transactional, muscular hemispheric hegemony: grabbing what it wants in its “near abroad” and openly defying outside interference.

The Maduro extraction is “Patient Zero” of this doctrine. Venezuela sits on the world’s largest proven oil reserves (about 241 billion barrels), and by physically seizing Maduro and decapitating his regime, Washington signaled it will no longer merely sanction adversarial governments – it will remove them if they stand in the way of U.S. resource needs. Almost immediately, Venezuela’s state oil firm (and de facto its vast petroleum output) came under U.S. control. President Trump boasted that Caracas would “hand over 30–50 million barrels of oil to the United States, with the proceeds controlled by me, as President”, effectively turning a sovereign nation’s assets into a client supply depot. This represents a dramatic escalation from “America First” isolationism: rather than withdrawing, the U.S. is doubling down in its hemisphere with offensive resource securitization. Analysts at Eurasia Group flagged “The Donroe Doctrine” as a top global risk for 2026, warning that “heavy-handed American tactics will risk spurring backlash and unintended consequences” across Latin America.

For corporate boards, the Donroe Doctrine epitomizes “geographic triage” – a world where U.S. policy draws stark lines on the map. Washington has effectively declared the Western Hemisphere a “Fortified Sanctuary” for U.S. interests. Under what one might call a “Trump Corollary” to the doctrine, any presence of rival powers (China, Russia, Iran) in the Americas – be it port ownership, mining stakes, or telecom networks – is cast as a direct national security threat and targeted for expulsion. This suggests foreign companies aligned with those powers could face sudden expropriation or military action in Latin American jurisdictions. Meanwhile, U.S. companies are explicitly favored, backed by American military might as needed. The U.S. is essentially leveraging its unparalleled hard power in the hemisphere (which no outside power can currently counter) to create a protected sphere for American capital. In Bremmer’s analysis, this isn’t a return to orderly spheres of influence but rather “the law of the jungle, not grand strategy: unilateral power exercised wherever [the U.S. president] thinks he can get away with it, uncoupled from the norms, processes, alliances, and institutions that once gave it legitimacy.” The implications are twofold: companies must recalibrate regional risk (e.g. evaluate Latin America not as an open emerging market, but as a U.S.-dominated arena prone to shocks), and they must prepare for retaliatory dynamics (such as nationalist backlashes or counter-moves by China/Russia in their own spheres). In short, the United States’ domestic political revolution – a “U.S. political revolution” that has eroded many checks and balances – is translating into a new era of international volatility. The U.S. is tearing down the very global order it built, and doing so in a way that prioritizes short-term wins over long-term stability. This introduces considerable process risk: abrupt policy lurches, extraterritorial enforcement, and the demise of prior diplomatic rules.

The Mearsheimer Audit: Metabolic Exhaustion and Mandatory Retrenchment

While Bremmer views America’s disruptive pivot as a conscious policy choice driven by Trump’s worldview, political realist John Mearsheimer and fellow structural realists see it as an almost inevitable consequence of material constraints. From Mearsheimer’s perspective, the United States has simply hit the “metabolic limits” of being a globe-straddling hegemon. Decades of overextension – military interventions, alliances, and economic burdens – have eroded the country’s underlying capacity to sustain primacy. The cold numbers are striking: by 2025 the U.S. national debt had ballooned to roughly $35 trillion, more than 120% of GDP, creating mounting fiscal pressures. Core industrial base indicators (from manufacturing output to supply chain self-sufficiency) have deteriorated in the face of rising competitors. In Mearsheimer’s terms, the U.S. is now entering an era of “offshore balancing” by necessity – forced to pull back and secure its home front because it can no longer everywhere at once.

Mearsheimer has sharply criticized Washington’s recent behavior as symptomatic of an empire in decline. “U.S. foreign policy today represents a rushed attempt to re-assert dominance over a world that is rapidly slipping beyond Washington’s control,” he observed in late 2025. The Donroe Doctrine itself can be seen as evidence of this “metabolic inversion”: the U.S. turning inward to its hemisphere and resorting to coercion because its global leverage is waning. As America doubles down militarily in Latin America and concurrently distances itself from long-time European and Asian allies, it exposes a structural crisis. Mearsheimer stresses that intensifying unilateral military actions (like striking adversaries without allied support or regard for international law) and shunning allies are accelerating the erosion of U.S. global power. The departure from multilateralism – once a source of U.S. strength – leaves America isolated, while rivals like China benefit by “letting its chief rival undermine itself and win by default”.

From a structural-realist audit, the United States’ 2026 posture is not a masterstroke of strategy but a sign of imperial overstretch entering its endgame. The country is, in effect, liquidating its 20th-century “strategic surplus” (alliances, goodwill, economic dominance) to shore up a beleaguered core. We can think of the U.S. pivot to a fortified hemisphere as a kind of “strategic bankruptcy proceeding”: Washington is cashing in its remaining chips to consolidate what it can. Mearsheimer would argue this attrition of power was predictable. In his view, great powers ultimately must retrench when their economic and military edge diminishes. The U.S. in 2026 can no longer afford to be the guarantor of Europe’s security, the stabilizer of the Middle East, and the balancing force in East Asia simultaneously. Indeed, America’s relative decline is confirmed by global perceptions: allies now openly question U.S. reliability, and adversaries test its limits. Mearsheimer noted that as the U.S. withdraws or behaves erratically, “the message [to Europe] is: ‘You are on your own’”. The NATO alliance is weakened and European leaders are grudgingly waking to the reality that they must fend for themselves (a point we’ll revisit under “narrative emancipation” in Section IV).

What does this mean for business strategy? First, boards should prepare for U.S. policy zig-zags as symptoms of internal strain. A government facing “metabolic exhaustion” may take drastic short-term actions (trade wars, debt monetization, sanctions or even debt default threats) that roil markets. Second, the financial risks of America’s exhaustion cannot be ignored. The specter of a debt crisis or currency turbulence is no longer theoretical. In fact, a recent U.S. National Security Strategy scenario implied that a disorderly spike in U.S. Treasury yields (due to debt fears) could itself become a geopolitical risk. Companies with heavy exposure to U.S. assets or dollar funding must hedge against that tail risk – for example, by diversifying reserves into “safe haven” stores of value like gold or other currencies. Third, Mearsheimer’s logic implies a multipolar investment outlook: as the U.S. pulls back, other powers (China, India, the EU, etc.) will assert in their regions. For a global firm, this means adjusting strategic focus and resource allocation to a world where no single market guarantees stability. It would be prudent to reassess assumptions such as the inviolability of U.S. treasury bonds, the continuity of U.S.-led trade frameworks, or the security umbrella in East Asia. In summary, the realist audit counsels prudence and austerity: shore up balance sheets, avoid over-reliance on a declining hegemon, and brace for harder bargains in a more fragmented international system. The U.S. retreat is not a temporary tantrum but a structural inflection point – one that boards should treat as a permanent change in the rules of the game.

“Connectivity is Destiny”: The Khanna Perspective on Autonomous Corridors

Focusing solely on the “Eagle in triage” – the United States clenching its hemisphere – risks missing the other half of the 2026 story: the surging growth of new inter-regional connections that bypass traditional geopolitical chokepoints. Global strategist Parag Khanna offers a fundamentally different lens: while nations play tug-of-war, the world’s underlying economic links are reconfiguring in a way that diminishes the importance of old political boundaries. As Khanna famously argues, “Connectivity, not geography, is destiny.” In his view, we are witnessing the maturation of a “global network civilization” where supply chains, infrastructure corridors, and digital networks matter more than territorially defined blocs.

By 2026, this trend of “Asianization” of the world economy has reached a decisive phase. Asia’s influence is not just about China or one country’s rise; it is a system-wide integration. Consider that already by the mid-2020s, Asia (broadly defined) accounted for roughly two-thirds of global trade flows, and its internal trade and investment continue growing faster than any trans-Pacific or trans-Atlantic links. Major Asian and Middle Eastern players – India, Southeast Asia (ASEAN countries), the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, Japan, South Korea – have been investing massively in connecting to each other via new land and sea corridors. Dr. Khanna points to a proliferation of autonomous “Middle Power” corridors: multi-modal transport routes, energy pipelines, fiber-optic cable networks, and financial circuits that link, for example, the Middle East’s capital and energy hubs to South and East Asia’s manufacturing and consumer markets. These are “functional geographies” that often cut across or ignore political boundaries. For instance, the planned India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor, new Central Asia–South Asia transport links, or the expansion of GCC-Asia energy supply chains all reflect this connectivity paradigm – where the aim is to create resilient routes for goods, data, and money that avoid single points of failure or dependency on U.S./China choke points.

Khanna’s connectivity maps reveal a world being redrawn by these linkages: a patchwork of what he terms “competitive connectivity” zones, in which cities and regions compete to be vital nodes of commerce. It’s a world where, as one endorsement of Khanna’s work put it, “flow prevails over friction”. The effect is that many medium-sized countries now have greater strategic autonomy than before. The Middle Powers – from the UAE and Saudi Arabia to Indonesia, Turkey, Brazil, and Nigeria – no longer see themselves as mere pawns of superpowers. They are leveraging multi-alignment: partnering wherever advantageous, diversifying their alliances, and in some cases collaborating with each other to create alternatives to superpower-dominated systems. For example, the UAE can host both U.S. and Chinese military or commercial facilities and use its logistical clout to mediate between powers. India participates in forums with Russia/China (BRICS, SCO) even as it joins U.S.-led initiatives, all while investing in its own infrastructure influence in neighbors like Sri Lanka and Oman. No longer “vassals,” these countries act as global hubs that attract investment from all sides and serve as critical transit points that neither Washington nor Beijing fully controls.

For business leaders, Khanna’s perspective underscores opportunity and resilience: the companies that thrive will be those that tap into these new corridors and hedge against geopolitical segmentation by “going local-global.” A few strategic implications stand out:

- Invest in the New Hubs: Identify the emerging hub cities and zones along these autonomous corridors – e.g. Dubai/Abu Dhabi in the GCC, Singapore and Jakarta in ASEAN, Mumbai in South Asia – and establish a substantive presence there. These locations offer “escape hatches” from great power conflicts, meaning if one superpower market becomes difficult, these hubs allow continued access to growth via alternate routes. For instance, if U.S.-China trade is restricted, a firm might route its supply chain through India and the Middle East (where no single power can block it end-to-end).

- Local-for-Local Supply Chains: Embrace what Khanna and others call a “local-for-local” strategy – producing and sourcing within key regions for those regional markets. Rather than a single global supply chain optimized purely for cost, develop semi-autonomous regional supply loops (Americas, Europe, Asia) that can function even if inter-regional links break. This strategy is already emerging as a resilience play: by 2026, a significant share of manufacturers have increased localization of critical components (semiconductors, battery materials, etc.) to reduce exposure to export controls or shipping disruptions. A white paper co-authored by Khanna notes that “Already, Asia’s exports and imports account for two-thirds of global trade… (and) its middle class… 3 billion by 2030”, highlighting the reward for committing to these markets. In essence, follow the demand – which is increasingly centered in Asia and other high-growth regions – and build capacity there rather than assuming a unified global production line will suffice.

- Hedge the Superpower Dueling: The connectivity paradigm does not mean geopolitics is irrelevant – rather, it means companies should hedge against superpower duopolies. The U.S.-China rivalry (from 5G technology to payment systems) creates pressure to choose sides on certain standards and platforms. But many middle countries are developing parallel systems (for example, alternative payment networks, dual-use telecom infrastructure) that allow more flexibility. Businesses can adopt a “bi-module” approach: be capable of operating within either bloc’s standards if needed, and even help middle players build neutral platforms. Khanna’s work suggests the most resilient firms “unscramble” traditional borders, finding ways to operate between spheres. A practical example is diversifying cloud infrastructure across U.S. and Chinese providers and investing in up-and-coming regional clouds or data centers in neutral territories (like India or Indonesia) to ensure continuity no matter which digital regime dominates.

In summary, the Khanna thesis provides a counter-balance to gloom about U.S. decline: even as old geopolitical pillars shake, new bridges are being built worldwide. Globalization is not dead; it has just taken on a new shape – less American, more distributed, often more under-the-radar. For the C-suite, connectivity is destiny means that mapping your firm’s future must involve mapping the world’s new silk roads, energy conduits, and information highways. In Khanna’s own words, “We’re accelerating into a future shaped less by countries than by connectivity… and the most connected powers, and people, will win.”. The imperative is to ensure your organization is among those connected winners, not stranded in a decoupling isolate.

Executive Synthesis: Embracing the Dual Reality

Reconciling the above perspectives yields a nuanced strategic outlook: the world is fragmenting and integrating at the same time. The United States’ tempest – its retreat into unilateral dominance of the Americas and the attendant geopolitical vacuum elsewhere – creates volatility, conflict risk, and uncertainty. Yet beneath that surface turmoil, networks of trade, technology, and talent are quietly reweaving a new order, one that is not unipolar but multipolar and multi-nodal. C-level leaders must internalize this dual reality. On one hand, they need to harden their enterprises against volatility: anticipate policy shocks from Washington (and other capitals), build financial resilience, and avoid complacency about the stability of legacy institutions. On the other, they should lean into the opportunities of functional connectivity: forge partnerships in rising regions, leverage technology to bridge distances, and innovate business models for a world where growth comes from many places at once.

The synthesis of Bremmer, Mearsheimer, and Khanna suggests a guiding mantra for 2026: Think like a hedgehog and a fox. The “hedgehog” aspect is to have a unifying big-picture strategy – e.g. committing to resilience and strategic autonomy as core principles. The “fox” aspect is agility – being ready to pivot among diverse markets and supply lines as conditions change. For example, a hedgehog strategy might be “achieve supply chain independence from any single country by 2028,” while the fox tactics involve multi-sourcing critical components, keeping excess inventory as buffer, and using AI to constantly reroute logistics based on risk signals. Another unifying strategic goal might be “capture the Asian consumer”, pursued by tailoring products to local tastes, hiring regional talent, and engaging in public-private initiatives in Asia – all while insulating the business from any fallout of U.S.-China tensions via corporate structure (e.g. possibly separating China-facing subsidiaries).

In practical terms, boards should create a “dual reality dashboard” that monitors both geopolitical risk indicators (coups, sanctions, conflict escalation indexes) and connectivity indicators (trade volumes on new routes, internet bandwidth growth, regional GDP share shifts). This dual monitoring reflects the world’s dialectic: crises and connectivity evolving in tandem. As we move to Section II, we’ll add the fourth expert perspective – technology – into this mix, which will further highlight how decision-makers can harness advanced tools to cope with these complexities. But even at this stage, one message is clear: embracing the dialectics of disorder is a 2026 leadership requirement. Executives must neither be paralyzed by the breakdown of the old order nor blinded by the excitement of new markets. Instead, they must be both realists and futurists – balancing an understanding of power politics’ harsh realities (Mearsheimer) and near-term risks (Bremmer) with a vision for long-term global opportunity (Khanna). The payoff is clarity: knowing where to shore up defenses and where to push boldly ahead, in order to ensure the company’s longevity and growth in an era of permanent uncertainty.

II. The Intelligence Layer — Extractive AI vs. Living Intelligence

If geopolitics is one axis of disruption in 2026, technology – especially artificial intelligence (AI) – is another equally transformative axis. We are entering what futurist Amy Webb calls the era of “Living Intelligence”, where AI systems, connected devices, and biotechnologies converge to create autonomous, adaptive networks that can learn and act in real time. Yet alongside this promise comes peril: the rapid commercialization and hype around AI have spawned “extractive” AI models that threaten to manipulate and even erode human decision-making. In the boardroom, this translates to a critical strategic tension: how to harness AI for faster, smarter decisions and operational resilience, while guarding against the risks of algorithmic distortion, intellectual capture, and security vulnerabilities. This section examines that tension through two lenses: Bremmer’s warning about the near-term risks of AI mis-use (“AI eats its users”), and Webb’s foresight into the next wave of AI-driven transformation (the shift from mere data analysis to acting intelligences). By understanding both, executives can better formulate an “intelligence strategy” that maximizes the upside of these technologies while maintaining clarity and control.

Bremmer’s Warning: “AI Eats Its Users” – The Rise of Extractive AI

In Eurasia Group’s Top Risks 2026 report, one entry stands out as a novel socio-technological threat: “AI eats its users.” Despite the cheeky phrasing, Bremmer’s message is serious – he posits that AI, as deployed by leading companies under current pressures, could become as destabilizing as social media, only worse. The crux of the risk is what he terms “Extractive AI.” Faced with sky-high valuations and investor expectations, AI platform companies (from search engine providers to chatbot makers) may be tempted to monetize aggressively in ways that compromise integrity. Bremmer highlights the example of ads or sponsored content embedded in AI chatbot responses, where unlike a Google search result there is “no way to distinguish neutral information from paid influence.” In other words, AI systems that users turn to for advice or knowledge could slyly steer those users’ behavior – blurring the line between unbiased assistance and manipulation.

This phenomenon leads to what Bremmer calls “cognitive capture.” Social media in the 2010s captured our attention; AI has the potential to capture our cognition – “programming behavior, shaping thoughts, and mediating reality”, as he puts it. The near-term threat isn’t some future superintelligent machine turning evil; it’s the slow creep of human thinking being hacked by algorithmic content. Imagine millions of employees relying on an AI assistant for daily work tasks: if that AI is subtly nudging them towards particular products, political views, or corporate loyalties due to behind-the-scenes sponsorships, the effect on society could be profound. Bremmer’s blunt assessment is that AI could precipitate a “decline of thinking, feeling, and social humans” if it displaces our own critical reasoning with a feed of imperceptibly biased outputs. In 2026, we already see early signs: certain AI-driven apps have been caught quietly inserting promotional suggestions into user interactions, and anecdotally, people tend to over-trust AI-written answers, especially when delivered fluently.

For businesses and boards, Bremmer’s warning carries multiple implications:

- Trust as a Vulnerability: Companies that use AI to interface with customers (chatbots for support, AI-curated news feeds, etc.) must be extremely careful. If your AI-driven service tricks users or is perceived as manipulating them, the reputational fallout and regulatory backlash could be severe. In the EU and other jurisdictions, regulators are drafting rules to require transparency in AI outputs (e.g. labeling AI-generated content, disclosing when recommendations are paid). Boards should push management to implement ethical AI guidelines now – such as clear disclosure of AI advertising and robust content validation – not just as compliance but to preserve trust equity.

- Internal Decision Distortion: Beyond customer-facing AI, Bremmer’s point suggests a risk of decision-maker reliance on AI that subtly mis-optimizes for corporate interests over broader good. For instance, an AI analytics tool might highlight data that supports a CEO’s preconceived plan (because it was trained on past internal decisions) while omitting contrarian indicators – yielding a form of confirmation bias at scale. If AI begins to “mediate reality” for executives themselves, it could dull the strategic intuition that leaders cultivate. To counter this, companies should avoid black-box AI in critical decision loops; instead, maintain diverse information sources and encourage a culture of questioning AI outputs (what Webb calls keeping a “human in the loop” for interpretation).

- Social Stability and Labor: The external risk is that extractive AI contributes to societal instability (e.g. deepfake-driven misinformation, AI-tailored propaganda). Bremmer includes this under political risk because a population “programmed” by customized AI content is one ripe for polarization and unrest. Firms might think this is beyond their remit, but any large employer must consider workforce implications. Are employees being influenced by AI-recommended content that stokes conflict or reduces morale? Could AI-generated misinformation spark protests that disrupt operations? These scenarios are no longer far-fetched. Corporate leaders should therefore engage in industry consortia for AI governance, supporting norms or regulations that prevent the worst abuses (much like businesses eventually rallied to combat social media disinformation once it began impacting stability).

In summary, Bremmer’s AI risk is a caution that the short-term incentives of the tech industry can undermine long-term societal resilience. The year 2026 may be a peak of AI hype and profit-chasing. Boards must ensure that in pursuing the productivity and profit gains from AI, they do not inadvertently contribute to a “race to the bottom” that could undercut the very consumers and communities they rely on. As the saying goes, if you’re not paying for the product, you are the product – Bremmer warns that with AI, even if you are paying, you might still become the product. Guardrails, transparency, and human oversight are the watchwords to keep AI as a tool for empowerment rather than a tool of exploitation.

Webb’s Synthesis: The Era of “Living Intelligence” – AI that Senses and Acts

Contrasting with Bremmer’s focus on immediate risk, Amy Webb takes a horizon-scanning perspective: she looks at where the technology is headed and how organizations can prepare for (and shape) what’s coming. According to Webb, we stand at the dawn of “the era of Living Intelligence,” an emerging paradigm in which artificial intelligence combines with advanced sensors and biotechnology to create systems that are literally life-like – they can sense their environment, learn and adapt continuously, and even evolve their capabilities over time. Webb describes Living Intelligence (LI) as “a new system of continual data ingestion, decision-making, and action” at scale. In practical terms, this means AI is moving beyond the screen and the cloud, and embedding into the physical world around us. Intelligent sensors in our cities, homes, factories, and even inside our bodies (via biotech) will feed AI algorithms that don’t just analyze but also act autonomously – adjusting logistics flows, optimizing energy grids in real-time, personalizing healthcare on the fly, and so forth.

One key development Webb highlights is the rise of “Large Action Models” (LAMs), which succeed today’s large language models (LLMs). If LLMs like GPT-4 excel at generating text (“talking”), LAMs are designed for “doing.” These AI agents interface with the world: they can execute transactions, control robots, trigger workflows, or orchestrate other software – all based on higher-level goals set by humans. As a 2024 SXSW tech report summarized, “LAMs represent a shift from predicting speech to predicting actions and behaviors. Numerous sensors in our environment will be required to collect the data necessary for these predictions.” In Webb’s view, this is not speculative; the early signs are here. For example, self-driving car AI takes actions in the real world, smart factory systems autonomously adjust machinery based on sensor inputs, and even finance algorithms automatically execute trades. What’s coming is the scaling and convergence of these capabilities across domains. Imagine a supply chain AI that detects a demand surge (from retail sensors) and automatically reroutes shipments, raises factory output via IoT commands, and negotiates new raw material purchases via an online marketplace API – all without waiting for a human in the loop. That would be a rudimentary instance of “living intelligence” in enterprise. By late 2025, a Deloitte survey predicted that 75% of companies may be investing in such “Agentic AI” capabilities by 2026, deploying autonomous software agents across business processes. This underscores that businesses are indeed pushing toward AI that doesn’t just advise, but acts on decisions.

For Amy Webb, the advent of Living Intelligence is fundamentally an opportunity – but one that requires a new mindset and metrics in the boardroom. She argues that companies must move beyond reactive, hype-driven adoption of tech (chasing each fad) and instead develop “Quantitative Foresight” disciplines. Quantitative foresight means using data and models to systematically anticipate future scenarios, effectively simulating decisions before making them. With rich real-time data and AI agents, leadership teams can dramatically shorten decision cycles. Webb suggests measuring “Decision Speed” as a key performance metric – how quickly can your organization detect a change and respond effectively? In a living intelligence era, the fastest learners (organizations that can absorb new information and immediately translate it into action) will outcompete slower, rigid ones. She points to sectors like drug discovery and energy, historically slow-moving, where AI convergence is now slashing R&D times and boosting productivity. For instance, AI models can generate and test virtual drug compounds at a speed impossible for human scientists alone, and smart grids can autonomously adjust to integrate renewable energy in milliseconds. If your company isn’t leveraging these kinds of convergent tech, you risk falling behind those that do.

Webb’s recommendations for leaders can be summarized as building an “AI-native” strategic function in the organization:

- Invest in Sensor and Data Ecosystems: It’s not just about buying an AI software license. Companies should think about what data streams they can tap or create. This could mean deploying new sensors (in manufacturing, in products, in logistics), partnering to access external datasets, or even bio-monitoring for employee health and performance. The goal is to create the rich, real-world data foundation that powers living intelligence. Webb notes an “explosion of connected devices and sensors… to fuel AI with more real-world data”. If extractive AI (per Bremmer) is a danger, one antidote is having first-party data so your AI isn’t reliant on potentially biased external info.

- Empower AI to Act, But Set Boundaries: Webb envisions autonomous AI agents negotiating deals and managing tasks. We are already seeing prototypes – for example, AI assistants that can scan your email and automatically schedule meetings or purchase routine supplies. Boards should champion pilot projects for such “hands-free” automation in appropriate domains (e.g. inventory reordering, basic customer service resolutions). The competitive edge from this can be significant in efficiency. However, governance is key: rules of engagement must be coded in. For instance, an AI agent may have a spending limit or require human sign-off above a threshold. The company should define ethical guidelines so that AI actions align with corporate values and legal compliance. Deloitte’s report suggests that orchestrating these agents “effectively and safely” will be critical to unlocking their value.

- Cultivate AI Fluency in Leadership: Webb often emphasizes that leaders can’t treat AI as a black box managed solely by IT. In 2026, strategic decisions are technological decisions. Boards should ensure at least some directors and top executives deeply understand AI capabilities and limitations. This might involve continuing education, bringing AI experts into strategic planning sessions, or even having a “futures council” in-house. A recent study found 75% of companies now factor AI into hiring decisions for executives, indicating that AI fluency is becoming a required leadership skill. The CEO need not code neural nets, but they should grasp concepts like training bias, model drift, or data privacy trade-offs to steer the company wisely.

In essence, Webb’s foresight suggests that the firms that survive and thrive in the coming years will be those that think of themselves as living, learning organisms. She even labels the current cohort of adults “Generation T (Transition),” emphasizing that everyone from factory floor to C-suite has to participate in guiding the tech-driven societal transition. Rather than fear AI or worship it, Webb encourages a stance of proactive design: use strategic foresight to shape how AI is implemented so that it augments human capabilities and enterprise resilience. With proper vision, Webb believes AI can become an “everything engine” that drives positive outcomes across the business – from efficiency and innovation to new revenue models – instead of a runaway engine that drags us into chaos.

Bridging the Divide: Toward an Ethical, High-Speed Intelligence Layer

Taken together, Bremmer’s and Webb’s perspectives on AI form a two-sided coin: risk and reward, caution and ambition. The task for leadership is to build an “intelligence layer” in their strategy that captures the tremendous upsides of advanced AI while diligently mitigating its downsides. A few bridging principles emerge:

- Transparency & Control: As AI becomes more embedded in operations (decision-making, customer interactions, etc.), companies should institute transparency measures by design. This might mean regular audits of AI decisions, bias testing, and making the AI’s criteria explainable to both managers and possibly customers. For example, if an AI model is used to screen loan applications or job candidates, be prepared to explain in plain terms how it decides – to avoid the black-box syndrome that could lead to unfair outcomes or reputational harm. Control also means having a “kill switch” or manual override in critical systems. No autonomous process should be completely unfettered, especially in initial stages.

- Human Intelligence Augmentation: Encourage a culture where AI is seen as a collaborator for human workers, not a replacement in total. Webb’s future has AI taking over rote tasks, which ideally frees up humans for creative, strategic, or relationship-centric work. Communicate this vision to employees to reduce fear and resistance. Offering retraining programs for employees to learn to work effectively with AI tools is crucial – e.g. training analysts to use AI insights in making recommendations, rather than just letting the AI decide. An optimistic example: AI can draft a market research report in seconds; a human can then spend their time interpreting implications and crafting strategy from it, a far more value-added use of their expertise.

- Security & Resilience: With greater connectivity and AI autonomy comes increased cyber and operational risk. A hacked AI agent could wreak havoc (imagine an AI managing your inventory being manipulated to send all stock to one location). Therefore, cybersecurity investments must scale up accordingly. This is part of Bremmer’s warning too – guardrails. Ensure your AI and IoT endpoints are secure, have fail-safes for anomalies (e.g. an AI suddenly making out-of-character decisions should trigger an alert and pause). Also plan for redundancy: if your intelligent system fails or goes offline, can humans or backup systems take over smoothly? Running periodic drills (akin to fire drills) for AI outages can build confidence that the “intelligence layer” adds resilience rather than a single point of failure.

- Ethical Alignment: Finally, explicitly articulate an AI ethics policy. This should align with your corporate values and stakeholder commitments (customer wellbeing, fairness, etc.). Questions to address include: What data is off-limits for our AI to use? What decisions will we not automate? How do we ensure AI outcomes don’t perpetuate discrimination? For instance, if our AI recruiting tool is found to disproportionately filter out minorities due to biased training data, what steps do we take? Who is accountable? An ethical framework, reviewed by the board, will guide teams as they deploy AI in various functions.

By building this robust intelligence layer, companies effectively inoculate themselves against Bremmer’s nightmare scenario (AI run amok with negative social fallout) while accelerating toward Webb’s dream scenario (AI as an empowering, efficiency-boosting co-worker). The year 2026 is likely a make-or-break period in this regard: those who get AI right will vault ahead, those who get it wrong may stumble badly. As a striking indicator, by 2026 three in four firms globally have made AI and automation their top capital investment, reflecting a consensus that you either adapt to this new intelligent era or risk irrelevance. The next section will integrate the insights from Sections I and II – geopolitics, connectivity, and technology – into a unified strategic matrix for decision-makers, providing a toolkit to evaluate moves through all these lenses.

III. The Quad-Axis Matrix for the 2026 Boardroom

The challenges of 2026 demand a multidimensional strategic approach. To avoid blind spots, leaders must simultaneously account for political volatility, power shifts, network resilience, and technological velocity. Drawing on the four experts we’ve discussed, we propose a “Quad-Axis Matrix” as a decision-making tool for the boardroom. This matrix synthesizes the divergent Denkschulen (schools of thought) of Bremmer, Mearsheimer, Khanna, and Webb into an evaluative framework. By filtering every major strategic choice through each of these four axes, executives can ensure they are not over-indexing on one perspective while ignoring others. The ethos is “Clarity, not Urgency”: instead of reacting frantically to the latest crisis or trend, use the matrix to clearly map how a given action positions the company across the fundamental dimensions of risk and opportunity in 2026. Below we outline each axis with its core question, the current drivers on that front, and the recommended strategic posture (i.e., how a company should respond).

- Axis I: Volatility (Process Risk – Ian Bremmer’s lens)Key Question: How does this decision account for near-term political and policy volatility, especially emanating from the U.S.?2026 Drivers: U.S. “Political Revolution” and arbitrary policy swings (e.g. Donroe Doctrine interventions, trade wars by tweet), rising populism and nationalism in key markets, erosion of international norms.Boardroom Action: Hedge against political favoritism and instability. In practice, this means stress-testing strategies for a range of policy environments: if a friendly government suddenly turns hostile (or vice versa), can your business adapt? For instance, firms should avoid over-reliance on regulatory privileges that could vanish with regime change. Building bipartisan relationships and investing in government risk insurance (like political risk insurance for assets in volatile countries) are prudent. Also, consider the “personalization” of policy risk – when leaders like Trump govern by personal decree, companies can get caught in the crossfire of score-settling. So keep a low political profile and diversify government engagement. In sum, plan for policy shocks as a when, not an if.

- Axis II: Power (Structural Realism – John Mearsheimer’s lens)Key Question: Does this decision reflect the emerging balance (or imbalance) of hard power and economic power globally? Are we prepared for the structural constraints ahead?2026 Drivers: U.S. fiscal/industrial limits (“metabolic exhaustion”), the necessity for America to retrench (offshore balancing), the rise of peer competitors (China’s continued ascent, Europe’s quest for strategic autonomy, etc.).Boardroom Action: Fortify financial resilience and reduce exposure to hegemonic risk. For boards, a top item is auditing the balance sheet for vulnerability to a U.S. economic or currency crisis. With U.S. debt so high and monetary policy uncertain, ensure you can withstand, for example, a spike in interest rates or a sudden dollar fluctuation. Hedge with safe-haven assets – some firms are modestly increasing allocations to gold or cash in non-dollar currencies as a buffer. Additionally, reconsider supply chain and market exposure in light of superpower support: e.g., if the U.S. security guarantee is in doubt somewhere (say, Taiwan), what’s the contingency if conflict erupts or if the U.S. cannot intervene? This axis also implies investing in self-sufficiency where feasible: energy, critical materials, key technologies. Governments are doing “friendshoring” – companies can likewise friendshore or “ally-proof” their operations so that a single geopolitical pivot doesn’t cripple the business. Realistically assess power dynamics: if choosing between expanding in two markets, favor the one with more long-term stability or backing from a strong coalition. Essentially, don’t build the future of your company on a geopolitical sandbank.

- Axis III: Connectivity (Functional Geography – Parag Khanna’s lens)Key Question: Does this decision leverage the new connectivity corridors and hedges against fragmentation? Are we plugged into the flows that matter?2026 Drivers: “Asianization” of supply chains and capital flows, Middle Powers creating autonomous trade routes (GCC-Asia, ASEAN-India, etc.), digital connectivity (global internet vs splinternets) shaping market access.Boardroom Action: Prioritize proximity, control, and network diversity. Concretely, this means investing in local capacity in key hubs – for example, establishing R&D or production in the UAE/Saudi to serve Middle East and South Asia, or in Singapore/Vietnam for Southeast Asia. By being “in the network,” you gain intelligence and agility. Khanna suggests the most resilient firms unsnarl traditional borders. One way to do this is by participating in infrastructure consortia – e.g., co-finance a port or data cable that gives you assured throughput even if others are congested. Another imperative is to adopt “multi-local” strategies: tailor products to regional tastes (no more one-size global product if tastes are diverging), cultivate local partnerships and talent, and ensure compliance with local data and content norms so you aren’t shut out by sovereign tech regulations. This axis also encourages embracing redundancy for resilience: multiple routes, suppliers, or channels to reach any important market. If one door closes (due to sanctions or conflict), you have others open. In short, design your corporate footprint as a mesh network, not a hub-and-spoke dependent on headquarters or any single country. The payoff is that you can operate fluidly even in a balkanized world.

- Axis IV: Intelligence (Quantitative Foresight – Amy Webb’s lens)Key Question: Are we accelerating our adoption of convergent technologies to sense and respond faster than competitors? How does this decision improve our “decision intelligence”?2026 Drivers: AI “tech convergence” (AI + sensors + biotech = living intelligence), the emergence of Large Action Models enabling autonomous decision agents, an arms race in AI investment (with ~75% of companies ramping up AI deployments).Boardroom Action: Integrate AI-driven decision systems aggressively – but thoughtfully – into the enterprise. Webb would advise measuring “Decision Speed” as a core KPI. Boards should ask: How long do we take to detect a significant change and act on it? If it’s weeks and could be days, that’s a competitive gap. Invest in real-time data infrastructure and advanced analytics in areas like supply chain management, customer insights, and risk monitoring. For instance, implement AI that can autonomously reallocate inventory or re-price products in response to live demand signals. However, make sure to incorporate the guardrails from Bremmer’s insight: build AI ethics and oversight so that your adoption doesn’t lead to customer mistrust or regulatory intervention. Aim to use “Large Action Models” for internal efficiency – e.g., AI ops agents that handle routine tasks (IT self-healing, automated financial reconciliations). Free humans for higher-order tasks. At the same time, upskill your workforce to work alongside AI; a company is only as smart as its people-plus-machines combo. By 2026, some firms have created internal “AI councils” at the board level to guide and audit AI strategy, which can be a best practice. The mantra is don’t just have AI, wield it better than anyone else. If your competitors take 10 hours to adjust to a market shift and you take 2 hours because your AI-driven systems detected and adapted, you’ve gained a decisive edge. In volatile times, that agility can mean the difference between profit and loss.

By mapping any strategic initiative against these four axes, boards can visualize a balanced scorecard of readiness. For example, consider a decision like entering a new country or launching a new product line: The Volatility axis might raise questions of regulatory risk or populist backlash in that country (should we hedge or phase entry?). The Power axis would consider whether the move aligns with or avoids great power tensions (is this country in China’s sphere; will the U.S. be okay with us investing there?). The Connectivity axis checks if this expands our network resilience (does it plug us into a new corridor? Do we have alternative supply routes?). The Intelligence axis looks at how we can leverage tech for success (can we use AI to localize the product rapidly? Can we gather data from this expansion to improve overall foresight?). If an initiative scores well on all axes, it’s likely robust. If one axis flags a concern (e.g., great on tech and connectivity, but terrible on volatility due to political instability), the board knows to mandate mitigation plans or perhaps reconsider the move.

In essence, the Quad-Axis Matrix encourages what we might call 360-degree strategic vision. It pushes leaders to be comprehensive curators of information, much like an 'Oblique Gaze' approach: deliberately looking at problems from unusual but relevant angles to broaden the board's perspective. In doing so, an organization cultivates “Connected Intelligence” – the fusion of geopolitical savvy, network agility, and tech-powered insight into a single decision-making ethos. This is the antidote to the siloed, linear thinking of yesteryear’s strategy. And given the complexity of today’s environment, it may well be the only path to not just survive, but thrive amid the turbulence.

IV. Strategic Implications — From Attrition to Autonomous Resilience

Synthesizing the four perspectives isn’t a mere academic exercise; it yields concrete strategic shifts that organizations should undertake. The implications span operating models, risk management, and leadership philosophy. Broadly, companies need to transition from a model of attrition to one of autonomous resilience. Attrition here refers to grinding down vulnerabilities through incremental defensive measures – a posture that is no longer sufficient when disruptions are fast and non-linear (be it a sudden geopolitical shock or an exponential tech change). Autonomous resilience, by contrast, is a state where a company’s systems and people can self-adjust to shocks in real time, bouncing back or even thriving amid volatility. In this section, we highlight three strategic implication areas that stem from the 3+1 synthesis of our experts: (1) the Connectivity Hedge, (2) the Predictive Attrition Model, and (3) Narrative Emancipation as a leadership tool. Each represents a bridge from theory to practice – the moves a forward-looking C-suite should prioritize to master the NAVI (volatile, autonomous, variable, interconnected) world of 2026.

1. The Connectivity Hedge – **“Proximity and Control” Over Cost

In supply chain and market strategy, a clear implication of Khanna’s connectivity paradigm is that companies must re-optimise for resilience and access, even at the expense of pure efficiency. The old globalization playbook single-mindedly chased low costs (labor arbitrage, just-in-time inventory from cheapest supplier). The new playbook emphasizes “proximity and control.” Boards should ask: Where do we need to have physical proximity to ensure control over our fate? This often means bringing critical parts of the value chain closer (either geographically closer to home or closer to end markets) and/or internalizing capabilities that were previously outsourced. For example, if you rely on a single overseas supplier for a key component, consider dual-sourcing with one source in-region or investing in your own production facility for it, even if costs are higher. The reasoning is that a slightly higher steady-state cost is a worthwhile hedge against the probability of a severe disruption that could halt production entirely.

We already see this logic unfolding in industries like semiconductors (where companies are diversifying chip fabrication to more locations) and pharmaceuticals (building regional API manufacturing to avoid sole dependence on, say, China or India for drug ingredients). In a telling observation, the Eurasia Group noted that “the Western Hemisphere [being] elevated in U.S. strategy… looks like a 19th-century carve-up, but the world is too interconnected to carve up and too fragmented to hold together”. In business terms, this means you cannot count on unfettered global integration (carve-up attempts will happen), but you also cannot retreat to fortress operations (fragmentation has limits because interdependence is real). Thus, connectivity hedging involves securing alternative connections rather than severing all connections.

One powerful way to implement this is via multi-modal, multi-local infrastructure. As referenced earlier, the “local-for-local” production trend is key. A tangible target might be: “Within 2 years, achieve at least 60% localization of supply for each of our major product lines in each key market region.” In fact, in the Scurati CEO checklist, a recommendation is to reach “58%+ localization of ‘electric stack’ components” (for example, batteries, chips for EVs) in critical markets within 30–60 days of a new initiative. While the exact number will vary by industry, the spirit is to significantly raise local content to reduce exposure to transport chokepoints or export bans. Where local manufacturing isn’t feasible, the hedge might be holding higher inventory of critical inputs in-region – a reversal of just-in-time, more towards a just-in-case buffer stock. This runs counter to cost minimization but pays for itself the first time a geopolitical incident (like a sudden tariff or port closure) would have stopped production but doesn’t because you had the buffer.

Additionally, the connectivity hedge implies investing in the new Silk Roads rather than waiting on governments. For instance, a consumer goods company might join a consortium building a new warehouse network along an emerging trade corridor (say, Central Asia) to ensure it can reroute goods if traditional routes (via a conflicted Russia or a contested South China Sea) become unviable. According to Khanna, companies that do this “unscramble traditional borders” and effectively create their own lattices of exchange beyond the control of any single hostile power. It’s a kind of corporate geo-economic strategy: be present in as many of the key connectivity nodes as possible. Think of it like diversifying an investment portfolio – but here you’re diversifying geopolitical and logistical risk.

2. Predictive Attrition Management – **Fusing Foresight with Realism

We introduced earlier the idea of blending Mearsheimer’s and Webb’s insights: using technology to get ahead of the structural attrition problems that realism highlights. The result is what we can call Predictive Attrition Management. Accept that some attrition – degradation of capacity under strain – is happening (e.g., industrial supply chains wearing thin under trade wars, or talent pipelines drying in aging societies), and use AI and data proactively to mitigate those effects before they bite. By 2026, 75% of companies globally have made AI their top capital investment specifically to identify risks before they manifest as supply shocks or resource squeezes. This statistic, cited in an EY geopolitical outlook, signals that many firms are deploying predictive analytics for early warning. For example, companies are analyzing satellite imagery of reservoirs and crop fields to anticipate commodity price spikes (and then hedging or substituting materials in advance). Others are monitoring social media and local news via AI for hints of political unrest that could affect their operations, giving a lead time to adjust staffing or output.

In practical terms, predictive attrition might involve: setting up a “nerve center” in the organization – a cross-functional risk radar team empowered with AI tools – to continuously scan for emerging stresses on the company’s strategic resources. This team would look at things like: is a key supplier showing financial trouble (perhaps detected via AI reading of news or even financial data patterns)? Is there a subtle uptick in employee turnover in a critical division that might presage a talent crunch? Are any early indicators suggesting a government we rely on (for subsidies, contracts, etc.) may change policy or leadership (e.g., polls, unrest signals)? By catching these signs, the company can act: qualify a new supplier, start retention incentives for staff, shore up inventory, engage policymakers, etc., before a full-blown crisis. It essentially applies the OODA loop (Observe–Orient–Decide–Act) at scale with AI to shrink the observe/orient phase dramatically, yielding faster action.

Mearsheimer’s realism underscored “industrial attrition” – the idea that protracted strain (like a lengthy great-power rivalry) can slowly degrade a nation’s industrial base. Companies should assume something similar: a prolonged period of geopolitical tension and deglobalization could wear down corporate efficiency (through tariffs, inefficient duplication of processes, restricted talent mobility, etc.). Predictive management counters that by finding efficiencies through foresight. Amy Webb’s concept of measuring Decision Speed fits perfectly: if you can respond to attrition factors faster than others, you incur less damage. The goal is to prevent small fires from becoming infernos.

One concrete initiative many boards are pursuing in 2026 is investing in digital twins of their operations – detailed simulations that can stress-test how the system behaves under various scenarios. For instance, using a digital twin of your supply chain, you can simulate what if a particular country’s export went offline, or what if energy prices doubled, etc., and see which parts of your network fail first. Then you reinforce those parts now. This is a classic intersection of Webb’s quantitative foresight with Mearsheimer’s hard-headed risk realism: assume tough times, simulate them, bolster your defenses accordingly.

Another example: Mearsheimer might say an era of multipolarity could lead to more resource nationalism (countries hoarding or weaponizing resources). A predictive approach is to use AI to monitor global resource flows and identify signs of such hoarding early. If data shows country X suddenly importing way more grain than usual and halting exports, you can infer they might be preparing for a squeeze – so you secure contracts elsewhere. Some energy companies are using AI to predict OPEC decisions by analyzing patterns in shipping and production data, giving them a trading edge.

In summary, predictive attrition management means never fighting the last war. It’s about leveraging every technological advantage to see the next challenge before competitors or adversaries do, and adapting preemptively. It acknowledges structural decline pressures (be it a declining market or tougher competition) but refuses to be passive about them. Instead, turn long-term attrition into a series of manageable short-term problems that you tackle in advance.

3. Narrative Emancipation – **Realist Pragmatism in Leadership

The third strategic implication goes beyond hard operations and into the realm of leadership and organizational culture. If the world order and the business environment are fundamentally shifting, companies need a new narrative to make sense of it all – for their employees, investors, and other stakeholders. The term “Narrative Emancipation” comes from political thinker Luuk van Middelaar, who argues that Europe (and by extension organizations within it) must liberate itself from the “narrative shackles of a transatlantic order which died… and claim our place in the multipolar world as a polity worth defending.”. In a corporate context, narrative emancipation means breaking free from outdated assumptions and stories (e.g., “globalization is inevitable and always good,” or “we are the unchallenged leader in our market because that’s how it’s always been”) that no longer match reality. Instead, leaders must craft an honest, clear-eyed story of who the company is now, what challenges it faces, and why the strategic pivots being made are necessary for long-term success.

This is not just PR or feel-good messaging – it is a tool for alignment and resilience. As van Middelaar notes, “narrative offers a compass for navigating difficult trade-offs… it’s how short-term losses can be traded for long-term gains”. For example, you may need to exit a profitable market because it’s becoming politically untenable (a “short-term loss”). Without narrative framing, this looks purely negative to shareholders (“why are you giving up revenue?”). But if you communicate a narrative of realist pragmatism – e.g., “We are withdrawing from Market X because the growing geopolitical risks there threaten our core business; instead, we will double down in Markets Y and Z which align better with our strengths and the global trends” – you position it as a strategic reallocation for future stability (a “long-term gain”). The narrative provides context and justification that can maintain investor confidence and employee morale.

In 2026, we can foresee tough decisions like divesting from certain countries, reshoring facilities at higher cost, choosing principles like data privacy over some ad revenues, or reorganizing the company to cut legacy units. Each of these involves trade-offs that will meet internal resistance or external scrutiny. A CEO's most critical soft skill in 2026 is the ability to practice 'Realist Pragmatism' openly. That means telling it like it is – acknowledging, for instance, that the world is not going back to a pre-2020 “normal,” that some beloved projects might have to be shelved, that the company must evolve or decline. And importantly, framing the company’s identity in a way that is future-oriented: who are we in this new world? The narrative might emphasize resilience, innovation, and responsibility as core themes.

A concrete measure is for leadership to create what one might call a “State of the World and Company” address, at least annually, where they lay out how global changes (from climate to geopolitics to tech) are impacting the business and what strategic moves they are making in response. By doing so, leadership brings employees and investors along on the journey, rather than springing changes on them with no context. It treats stakeholders as adults who can understand complexity, which often earns their respect and buy-in. As van Middelaar implies, narrative is about constituting a “We” – giving people a sense they are part of a collective with a purpose in this evolving landscape. For a company, that could mean evolving the mission statement to something like: “In a world of unprecedented change, We (company name) exist to provide stability and innovation – we empower our customers to adapt through our products, and we commit to navigate the future with integrity and agility.” It sets a tone that change is the norm, not the exception, and that the organization is ready to face it.

Finally, narrative emancipation also has a defensive aspect: it inoculates against external narratives that might harm the company. In a polarized world, if you don’t define yourself, someone else will. Companies might be accused of being unpatriotic if they operate in a rival country, or of being monopolistic if they adopt certain AI, etc. By having a strong narrative (say, emphasizing how your global presence benefits communities or how your AI ethics are solid), you can better respond to or preempt such criticisms. In other words, narrative control is part of risk management.

In conclusion, the strategic implications of the Quad-Axis Synthesis push firms toward acting faster, decentralizing smarter, and leading braver. Resilience in 2026 is not a passive fortress but an active network – of assets, people, and ideas – that can flex under stress. Implementing a connectivity hedge builds that network; predictive foresight keeps it agile; and narrative emancipation ensures everyone in and around the network understands and supports the course you’ve set. With these in place, a company transforms from a rigid entity that fears change into a dynamic organism that feeds on change – turning challenges into catalysts for evolution.

Conclusion

Taken together, the perspectives of Ian Bremmer, John Mearsheimer, Parag Khanna, and Amy Webb provide a rich, multi-faceted strategic outlook for any C-level decision-maker trying to navigate the next decade. These thought leaders do not agree on everything – in fact, their emphases often differ – but that is precisely their value. In a world of such complexity, no single framework or forecast has all the answers. A comprehensive worldview requires integrating insights about political instability, security threats, economic trends, and technological disruptions. By examining these four lenses side by side, we can discern both points of convergence and constructive contradictions, yielding a more nuanced understanding of what lies ahead.

One striking commonality is the recognition that the world is in flux; the relatively stable orders of the past (whether the U.S.-led unipolar moment or the earlier bipolar Cold War) are giving way to a more uncertain configuration. Bremmer’s G-Zero world, Mearsheimer’s new cold war, Khanna’s multipolar connectivity, and Webb’s technological beyond all capture aspects of a reality where old assumptions are breaking down. There is a shared sense that disruption is the new constant – be it disruption of political norms, international power hierarchies, global trade patterns, or business models and technologies. For executives, this underscores the importance of building agility and resilience into their organizations. Long-term strategy can no longer assume a predictable environment; instead, scenario planning and adaptive management become critical. The convergence of these expert views suggests a few broad scenarios leaders should be ready for: a fragmented geopolitical landscape with higher risks of conflict (Bremmer and Mearsheimer), a continued push for market expansion and infrastructure in emerging economies (Khanna), and an acceleration of innovation that could upend competitive positions overnight (Webb).

At the same time, the differences in their outlooks are equally instructive. Bremmer offers a cautionary tale about the erosion of governance and the rise of volatility – a reminder to expect the unexpected in political affairs and to hedge against systemic shocks. Mearsheimer injects a dose of realpolitik, arguing that power politics and military considerations cannot be wished away by globalization or goodwill; his perspective suggests that prudent leaders should consider worst-case geopolitical contingencies (however grim) as part of risk management. Khanna, on the other hand, reminds us not to lose sight of opportunities: even as old centers of power falter, new centers are rising; even as some doors close, others open. His emphasis on Asia and the enduring force of globalization encourages companies to continue investing in growth, innovation, and cross-border relationships – albeit in a smarter, more geographically diversified way. Webb compels us to look forward and inward: forward to how emerging technologies will redefine industries, and inward to whether our organizations have the culture and foresight to adapt. She highlights that in a time of exponential change, competitive advantage will favor those who anticipate and shape technological trends rather than those who react late.

For a CEO or government leader, the blend of these viewpoints could translate into a holistic strategic agenda. Such an agenda might include:

- Geopolitical Risk and Resilience: Proactively monitoring geopolitical signals (using frameworks from Bremmer) and creating contingency plans for events like political upheaval, sanctions, conflict, or resource crises. This could involve everything from diversifying supply chains and securing critical inputs, to lobbying for sound public policy and international cooperation. The goal is to ensure that the company can withstand shocks emanating from political arenas – essentially, to become as “world-proof” as possible in a G-Zero context.

- Security and Geostrategic Awareness: Incorporating insights from Mearsheimer, companies – especially those operating globally – should deepen their understanding of great-power dynamics. Engaging in “strategic intelligence” efforts (or partnering with firms that provide such analysis) can help anticipate moves by major actors (US, China, EU, etc.) that might affect market access, regulation, or even physical operations. For example, a tech firm might closely watch US-China tech relations to foresee export controls, or a manufacturing firm might keep tabs on defense postures that could disrupt shipping lanes. Preparing for tail-risk scenarios (like conflict over Taiwan or a fragmented internet) could differentiate those who survive a crisis from those who falter. As Mearsheimer might say, hope for peace but prepare for rivalry.

- Global Growth and Diversification: Guided by Khanna’s perspective, leaders should continue to pursue global opportunities, especially in emerging markets. This means not over-concentrating on any single region – for instance, balancing engagements in North America, Europe, and Asia – and staying attuned to regional integration trends. If ASEAN is becoming a major economic bloc, or Africa is making strides in free trade, that should be on the radar. Khanna’s multi-alignment theme suggests businesses also practice a form of multi-alignment: maintaining relationships and compliance in multiple spheres of standards (e.g., being able to operate under both U.S. and Chinese tech ecosystems if needed, or meeting both EU and local regulations). Flexibility is key. The optimistic subtext here is that innovation and growth will continue globally, so companies should position themselves to capture upsides, not just batten down hatches against downsides.

- Technological Foresight and Innovation: Finally, inspired by Webb, companies must treat technology strategy as core to their mission, not an adjunct. This could mean establishing internal foresight teams or innovation labs, investing in talent and training for AI and data literacy, and forging partnerships with tech startups or universities. Cybersecurity and digital trust need to be pillars of the organization – not only to prevent breaches but to assure customers and partners in an era of deepfakes and data breaches. Webb’s work suggests asking tough questions: What if a competitor uses AI to drastically cut costs or personalize at scale – how would we respond? Are we prepared for a future where our product or service can be delivered in a fundamentally different way thanks to technology? Embracing such questions will help avoid the fate of companies that were upended by technology shifts they failed to foresee (the Kodaks and Blockbusters of the past). Moreover, Webb encourages a mindset of ethical and long-term thinking: technology will change society, and businesses that lead responsibly will not only mitigate risks but also build brand trust and loyalty.

There is a poignant quote circulated from Amy Webb’s recent commentary: “A leader’s job in 2026 is to ensure an organization can adapt when the code of business, nature, and truth itself starts to change.”. It captures the gravity and breadth of the leadership challenge today. The “code” of business refers to the fundamental assumptions about how we operate – many of which are indeed changing, whether through AI rewriting how we make decisions, or new norms around sustainability altering what consumers expect. The “code of nature” could hint at our environment and biology – which climate change and bioengineering are respectively threatening and transforming. The “code of truth” reflects the information ecosystem – fighting disinformation and maintaining credibility in the digital age. To adapt as these “codes” change, leaders must be scanners of horizons and orchestrators of agile responses.

In conclusion, the four perspectives we explored are not four separate truths, but four parts of one complex reality. By understanding Bremmer’s warnings of a leaderless order, Mearsheimer’s realist alarm at great-power flashpoints, Khanna’s vision of a resilient multipolar globalization, and Webb’s foresight into technological upheaval, decision-makers can craft strategies that are both robust and forward-looking. The world of the mid-2020s and beyond will undoubtedly test the resilience of enterprises and institutions. There will be shocks and surprises – political crises, security emergencies, economic reconfigurations, and technological jolts. No single expert – not even our four luminaries – can predict exactly how it will all play out. But by drawing on diverse insights and remaining flexible, C-level leaders can develop a kind of peripheral vision, catching sight of threats and opportunities from multiple angles before they converge.

In practice, this might mean scenario exercises that include, say, a Bremmer scenario (global governance breakdown), a Mearsheimer scenario (great-power standoff), a Khanna scenario (emerging market boom), and a Webb scenario (tech disruption). It means fostering a culture that is curious about the world, not narrowly focused on quarter-by-quarter metrics. It means investing in resilience – whether that’s supply chain redundancy, financial buffers, or employee skills – to weather storms. And crucially, it means maintaining optimism and agency: even if we live in disruptive times, human ingenuity and leadership can shape outcomes.

The perspectives of Bremmer, Mearsheimer, Khanna, and Webb collectively remind us that while no one can eliminate uncertainty, we can prepare for it, understand it, and even harness it. The goal for any executive team is to assemble the puzzle pieces into a coherent strategic picture for their organization. With political, economic, technological, and social pieces all in motion, that puzzle will never be static. But guided by experts who illuminate each domain, leaders can continuously update their mental map of the world. In doing so, they will be far better equipped to make wise decisions – the kind that not only protect their enterprise but also contribute to a more stable and prosperous future for all. In the final analysis, embracing a multi-perspective approach is itself a competitive advantage. It provides the breadth and depth of vision needed to chart a course through uncertainty – turning what could be an overwhelming fog of change into a navigable path forward, one informed decision at a time.Sources:

- Ian Bremmer, “America built the global order. Now it’s tearing it down.” GZERO Media (Jan 7, 2026) – Bremmer describes the U.S. unwinding of the post-1945 order and the “Donroe Doctrine” as Trump’s revival of Monroe Doctrine logic via military and economic coercion.

- TIME Magazine – “The Top 10 Global Risks for 2026” by Ian Bremmer (Jan 2026) – Outlines key risks including #1: U.S. Political Revolution (Trump’s systemic norm-breaking), #3: The Donroe Doctrine (U.S. primacy in Western Hemisphere with Venezuela example), and #8: “AI eats its users” (the threat of extractive AI models).